Who Said That a Great Nation Cannot Continuously Be Engaged in Wars

Nationalism was a prominent force in early 20th century Europe and a significant cause of World War I. Nationalism is an intense form of patriotism or loyalty to one's country. Nationalists exaggerate the importance or virtues of their home country, placing its interests above those of other nations.

Feelings of supremacy

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many Europeans, particularly citizens of the so-called Great Powers (Britain, France and Germany) had convinced themselves of the cultural, economic and military supremacy of their nation. According to historian Lawrence Rosenthal, this sentiment was:

"…a new and aggressive nationalism, different from its predecessors, [that] engaged the fierce us-them group emotions – loyalty inwards, aggression outwards – that characterise human relations at simpler sociological levels, like the family or the tribe."

The effects of this growing nationalism were an inflated confidence in one's nation, its government, economy and military power. Many nationalists also became blind to the faults of their own nation. In matters of foreign affairs or global competition, they were convinced that their country was fair, righteous and beyond fault.

In contrast, nationalists criticised rival nations to the point of demonisation, caricaturing them as aggressive, scheming, deceitful, backward or uncivilised. Nationalist press reports convinced many readers the interests of their country were being threatened by the plotting, scheming and hungry imperialism of its rivals.

Sources of nationalism

The origins of this intense European nationalism are a matter of debate. Nationalism is likely a product of Europe's complex modern history. The rise of popular sovereignty (the involvement of people in government), the formation of empires and periods of economic growth and social transformation all contributed to nationalist sentiments.

Some historians suggest that nationalism was encouraged and harnessed by European elites to encourage loyalty and compliance. Others believe that nationalism was a by-product of economic and imperial expansion. Growth and prosperity were interpreted by some as a sign of destiny. Other nations and empires, in contrast, were dismissed as inferiors or rivals.

Politicians, diplomats and royals contributed to this nationalism in their speeches and rhetoric. Nationalist sentiment was also prevalent in press reporting and popular culture. The pages of many newspapers were filled with nationalist rhetoric and provocative stories, such as rumours about rival nations and their evil intentions. Nationalist ideas could also be found in literature, music, theatre and art.

In each country, nationalism was underpinned by different attitudes, themes and events. Nationalist sentiment was fuelled by a sense of historical destiny and, therefore, closely tied to the history and development of each nation.

Military over-confidence

Nationalism was closely linked to militarism. It fostered delusions about the relative military strength of European nations. Many living in the Great Powers considered their nations to be militarily superior and better equipped to win a future war in Europe.

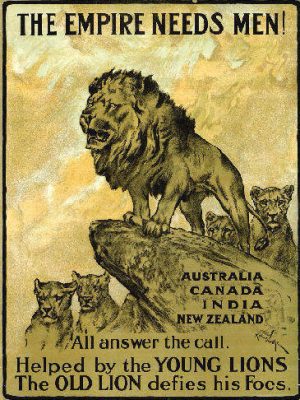

The British, for example, believed their naval power, coupled with the size and resources of the British Empire, would give them the upper hand in any war. Being an island also isolated Britain from invasion or foreign threat.

German leaders, in contrast, placed great faith in Prussian military efficiency, the nation's powerful industrial base, her new armaments and her expanding fleet of battleships and U-boats (submarines). If war erupted, the German high command had great confidence in the Schlieffen Plan, a preemptive military strategy for defeating France before Russia could mobilise to support her.

In Russia, Tsar Nicholas II believed his empire was sustained by God and protected by a massive standing army of 1.5 million men, the largest peacetime land force in Europe. Russian commanders believed the country's enormous population gave it the whip hand over the smaller nations of western Europe.

The French placed their faith in the country's heavy industry, which had expanded rapidly in the late 1800s. Paris also played great stock in its defences, particularly a wall of concrete barriers and fortresses running the length of its eastern border.

Attitudes to war

Nationalist and militarist rhetoric assured Europeans that if war did erupt, their nation would emerge as the victor. Along with its dangerous brothers, imperialism and militarism, nationalism fuelled a continental delusion that contributed to the growing mood for war.

By 1914, Europeans had grown apathetic and dismissive about the dangers of war. This was understandable. Aside from the Crimean War (1853-56) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), the 1800s was a century of comparative peace in Europe. With the exception of France, defeated by the Prussians in 1871, the Great Powers had not experienced a significant military defeat for more than half a century.

For most Europeans, the experiences of war were distant and vague. The British and French had fought colonial wars in Africa and Asia but they were brief conflicts against disorganised and underdeveloped opponents in faraway places. Militarism and nationalism revived the prospects of a European war, as well as naivety and overconfidence about its likely outcomes.

'Invasion literature'

By the late 1800s, some Europeans were almost drunk with nationalist sentiment. In some respects, this was a product of overconfidence fuelled by decades of relative peace and prosperity.

Britain, for example, had enjoyed two centuries of imperial, commercial and naval dominance. The British Empire spanned one-quarter of the globe and the lyrics of a popular patriotic song, Rule, Britannia!, trumpeted that "Britons never, never will be slaves". London had spent the 19th century advancing her imperial and commercial interests and avoiding wars. The unification of Germany, the speed of German armament and the bellicosity of Kaiser Wilhelm II, however, caused concern among British nationalists.

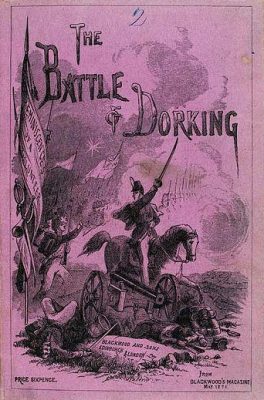

England's 'penny press' (a collective term for cheap, serialised novels) intensified nationalist rivalry by publishing incredible fictions about foreign intrigues, espionage, future war and invasion. The Battle of Dorking (1871), one of the best-known examples of 'invasion literature', was a wild tale about the occupation of England by German forces. By 1910, a Londoner could buy dozens of tawdry novellas warning of German, Russian or French aggression.

Invasion literature often employed racial stereotypes or innuendo. The German was depicted as cold, emotionless and calculating; the Russian was an uncultured barbarian, given to wanton violence; the Frenchman was a leisure-seeking layabout; the Chinese were a race of murderous, opium-smoking savages.

Penny novelists, cartoonists and satirists also mocked foreign rulers. The German Kaiser and the Russian Tsar, both frequent targets, were ridiculed for their arrogance, ambition or megalomania.

German nationalism

Attitudes and overconfidence in Germany was no less intense. German nationalism and xenophobia, however, had different origins to those in Britain.

Unlike Britain, Germany was a comparatively young nation, formed in 1871 after the unification of 26 German-speaking states and territories. The belief that all German-speaking peoples should be united in a single empire, or 'Pan-Germanism', was the political glue that bound these states together.

The leaders of post-1871 Germany employed nationalist sentiment to consolidate the new nation and gain public support. German culture – from the poetry of Goethe to the music of Richard Wagner – was promoted and celebrated.

German nationalism was also bolstered by German militarism. The strength of the nation, German leaders believed, was reflected by the strength of its military forces.

The nationalist Kaiser

The new Kaiser, Wilhelm II, became the personification of this new, nationalistic Germany. Both the Kaiser and his nation were young and ambitious, obsessed with military power and imperial expansion, proud of Germany's achievements but envious of other empires.

To Wilhelm and other German nationalists, the main obstacle to German expansion was Britain. The Kaiser envied Britain's vast empire, commercial enterprise and naval power – but he thought the British avaricious and hypocritical. London oversaw the world's largest empire yet manoeuvred against German colonial expansion in Africa and Asia.

As a consequence, Britain became a popular target in the pre-war German press. Britain was painted as expansionist, selfish, greedy and obsessed with money. Anti-British sentiment intensified during the Boer War of 1899-1902, Britain's war against farmer-settlers for control of South Africa. Ernst Lissauer's 1914 'Hassgesang gegan England' ('Song of Hate for England') is one of the best-known examples of anti-English sentiment.

Independence movements

As the Great Powers of Europe beat their chests, another form of nationalism was on the rise in southern and eastern Europe. This nationalism was not about supremacy or empire but the right of ethnic groups to independence, autonomy and self-government.

With the world divided into large empires and spheres of influence, many regions, races and religious groups sought freedom from their imperial masters. In Russia, more than 80 ethnic groups in eastern Europe and Asia had been forced to speak the Russian language, worship the Russian tsar and practice the Russian Orthodox religion.

For much of the 19th century, China had been 'carved up' and economically exploited by European powers. The failed Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1900 was an attempt to expel foreigners from parts of China. Later, resentful Chinese nationalists formed secret groups to wrest back control of their country.

Nationalist groups contributed to the weakening of the Ottoman Empire in eastern Europe by seeking to throw off Muslim rule.

Balkan nationalism

None of these nationalist movements contributed more directly to the outbreak of war than Slavic groups in the Balkans. Pan-Slavism, a belief that the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe should have their own nation, was a powerful force in the region. Slavic nationalism was strongest in Serbia, where it had risen significantly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Pan-Slavism was particularly opposed to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its control and influence over the region. Aggravated by Vienna's annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, many young Serbs joined radical nationalist groups like the 'Black Hand' (Crna Ruka).

These groups hoped to drive Austria-Hungary from the Balkans and establish a 'Greater Serbia', a unified state for all Slavic people. It was this pan-Slavic nationalism that inspired the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in June 1914, an event that led directly to the outbreak of World War I.

1. Nationalism was an intense form of patriotism. Those with nationalist tendencies celebrated the culture and achievements of their own country and placed its interests above those of other nations.

2. Pre-war nationalism was fuelled by wars, imperial conquests and rivalry, political rhetoric, newspapers and popular culture, such as 'invasion literature' written by penny press novelists.

3. British nationalism was fuelled by a century of comparative peace and prosperity. The British Empire had flourished and expanded, its naval strength had grown and Britons had known only colonial wars.

4. German nationalism was a new phenomenon, emerging from the unification of Germany in 1871. It became fascinated with German imperial expansion (securing Germany's 'place in the sun') and resentful of the British and their empire.

5. Rising nationalism was also a factor in the Balkans, where Slavic Serbs and others sought independence and autonomy from the political domination of Austria-Hungary.

Title: "Nationalism as a cause of World War I"

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/nationalism/

Date published: September 7, 2020

Date accessed: September 22, 2022

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

Source: https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/nationalism/

Post a Comment for "Who Said That a Great Nation Cannot Continuously Be Engaged in Wars"